The Ugly History of Beautiful Things

PERFUME

Sometimes it takes a touch of darkness to create something alluring

If given the choice to smell like whale excrement or delicate white flowers, few people would chose the first option. Bile, feces, vomit, and animal oils sound as though they would smell repulsive. The words conjure up scent memories of that time your dog released his anal glands on the duvet, or that summer you worked by the wharf and the August air was thick with the miasma of oily herring heads. Jasmine, on the other hand, sounds like a love song, a Disneyfied dream. Try, right now, to imagine the smell of blooming jasmine. Your memory, ill-equipped to locate scents in its baroque filing system, might pull up something syrupy sweet or softly floral. Is that how you want your body to smell?

Too bad: if you choose door number two, you'll walk away reeking of sharp vegetal tones tempered by a slightly earthy, foul scent. Jasmine absolute is an oily, semi-viscid, dark amber fluid that is denser and more concentrated than jasmine essential oil. Essential oils come from distilled, boiled, or pressed plant matter, while absolutes are traditionally made through a processed called enfleurage, which involves submerging the delicate blossoms or spices in fat before extracting their fragrance molecules into a tincture of ethyl alcohol. While it's a common ingredient in a natural perfumer's tool kit, jasmine absolute smells strange: complicated, beautiful, not entirely pleasurable. It reeks of indole (rhymes with “enroll”), an organic chemical compound also found in coal tar, human feces, and decomposing bodies.

If you choose door number one, you'll be blessed with the kiss of ambergris, a highly desirable natural substance that smells sweet yet rather marine, like vanilla and unrefined sugar mixed with seawater. The scent reminds me a little of the smell of my dog's paws – pink and light and animal. It smells like cashmere feels. Smelling ambergris is an innate pleasure, one that even an infant would recognize as enjoyable, like the first sip of sweet milk.

For more than a thousand years, humans have been adorning our bodies with animal products like ambergris and putrid-smelling plant derivatives like jasmine absolute. We apply off-putting materials to our bodies to enhance and mask our natural scents. Like dogs that roll in deer carcasses, humans seek to change our olfactory emissions by borrowing from other creatures. It's not always about simply smelling good: We want to smell complex, so that others will be compelled to keep coming back, like bees to a flower, to sniff us again and again, to revel in our scents, and draw ever closer to our warm, damp parts.

According to natural perfumer Charna Ethier, ambergris can smell like “golden light” or a “flannel shirt that has been dried on a clothes line on a warm summer day.” Although there are several types of ambergris (including gray, gold, and white), Ethier is referring to her own personal sample, which she characterizes as “soft, fresh, and ozonic.” Ethier is the owner of Providence Perfume Company in Rhode Island, and inside her well-stocked cabinet of olfactory curiosities, she keeps a single bottle of the precious stuff. Next to her 100-year-old cade oil (a foul-smelling liquid made from juniper trees, purchased at an estate sale) and below her collection of floral absolutes and herbal essences, she has stashed a bit of ambergris tincture. The clear glass vial contains a mixture of ambergris and alcohol that includes just 5 percent whale matter. In its pure form, this substance is a waxy gray ball of animal secretion, a floating fat-berg that is “more expensive than gold.” Unlike jasmine absolute, which plays a role in many of her perfumes, real ambergris is simply too expensive to use in a commercial product. “It's considered the miracle ingredient for perfumes,” she says. “It makes everything better.”

It's not always simply about smelling good: We want to smell complex, so that others will be compelled to keep coming back, like bees to a flower, to sniff us again and again, to revel in our scents, and draw ever closer to our warm, damp parts.

Ethier doesn't use any synthetics in her perfume, nor does she use animal products, though animal scents are a traditional ingredient in perfumery. Not only are these compounds expensive, but true mammalian products like musk, civet, and ambergris often come at a cruel cost. Whales have been murdered for their oily blubber and concealed stomach bile, civets are caged and prodded for their fear-induced anal gland secretions, and musk is harvested from the glands of slaughtered deer. Many people know that perfumers build their trade on the graves of millions of tiny white flowers, but fewer people realize they also bottle and sell the byproducts of animal pain and suffering. Perfumers who use synthetic materials are exempt, in a sense, as are those who use found or vintage materials. Ethier's ambergris is “quite old” and reportedly beach-found (“I hope it is,” she says). But even perfumes that use synthetic compounds or salvaged bile carry the whiff of death; the history of the industry is seeped in it, and that smell doesn't wash out easily.

There's a reason perfumers use these notes. They enhance the floral scents, undercutting lightness with a reminder of darkness. Animal products are the antiheroes in this drama – even when you hate them, you still, just a little, love them. That's how siren songs work, and ambergris sings the loudest. Once, Ethier made a perfume using her most prized ingredients. She mixed 100-year-old sandalwood essence with ambergris tincture and frangipane and boronia absolutes, two flowers native to Central America and Tasmania, respectively. It was the first time she'd used ambergris, and this one-off perfume was so lovely that “it was like gold-washing something.” She remembers wistfully, “It was so beautiful.”

Smell is the most underrated and mysterious sense. In her 1908 autobiography, The World I Live In, Helen Keller called scent the “fallen angel.” “For some inexplicable reason, smell does not hold the high position it deserves amongst its sisters,” she wrote. Keller mapped her world by smell – she could smell a coming storm hours before it arrived and knew when lumber had been harvested from her favorite copse of trees by the sharp scent of pine. In contrast to touch, which she called “permanent and definite,” Keller experienced odors as “fugitive” sensations. Touch guided her; scent fed her. Without smell, Keller imagined her world would be lacking “light, color, and the Protean spark. The sensuous reality which interthreads and supports all the gropings of my imagination would be shattered.”

We don't often think in terms of color and light when it comes to smell, perhaps because we have so few words for scent that we borrow from the lexicons of our other senses. Despite the fact that smell is our most ancient sense – our so-called “lizard brain” is also sometimes termed the rhinencephalon, literally the “nose brain” – it is also one that seems to elude language. “Smell is the mute sense, the one without words,” wrote Diane Ackerman in A Natural History of the Senses. “Lacking a vocabulary, we are left tongue-tied, groping for words in a sea of inarticulate pleasures and exaltation.” We've had eons to come up with words for the precise smell of fresh-turned earth or the exact scent of a blazing beach fire, and still the best we can do is earthy and smoky.

Perfumers have their own language, but their words have only recently begun to trickle down into popular culture through beauty magazines and blogs. Not only do perfumers and their superfans speak of absolutes, oils, and tinctures, but they can also rattle off compounds like coumarin and eugenol. A trained master perfumer (or “nose”) can pick out precise scents within a layered perfume. They don't just call something foul – they can pick out the pungency of musk or the reek of tobacco, ingredients that are delicious in small doses but overwhelming when used out of balance.

In my quest to understand the appeal of seemingly repugnant ingredients, I spoke with doctors who study the nose, perfumers who feed the organ, and even a zookeeper who spends her days breathing in the pure, undiluted scent of civet discharge. While they had various theories as to why darkness seems to be an essential element of beauty, they all agreed on one thing: It's all about context. In the right context, even the smell of death can be appealing. In the right context, vomit can be more desirable than gold. In the right context, with the right music playing in the background, you begin to root for the glamorous hit woman or the sardonic drug dealer.

They also agreed that sex is part of this equation, and it's the easiest explanation to trot out. But perfumery is also about more than just smelling nice and attracting a mate. It's about aesthetics, taste, and desire in a more general sense. We want to smell intoxicating, and truly intoxicating things are often a little bit nasty – they have an edge that cuts deeper than simple sensory pleasure. And despite how it may seem, encounters with the beautiful are rarely entirely enjoyable. If that were the case, Thomas Kinkade's light-dappled cottages would be considered the height of fine art, and we would all walk around misted lightly with synthetic jasmine and fake orange blossom. Instead, we adore the luscious gore of Caravaggio’s canvases and dab our pulse points with concoctions containing the miasma of swamp rot, the cloying smell of feces, and the pungent, tonsil-kicking fetor of death. Beauty is sharp, it is intense, and it comes at a cost. Just as desire and repulsion walk through the same corridors of our minds, so too do beauty and destruction move hand in hand. Whenever you find something unbearably beautiful, look closer and you'll see the familiar shadow of decay.

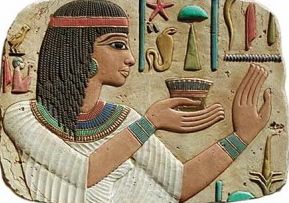

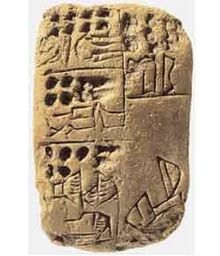

One of the first known perfumers in history was a woman named Tapputi-Belatekallim. According to clay cuneiform tablets dating back to 1200 BCE, Tapputi lived in ancient Babylon and likely worked for a king. The second part of her name, “Belatekallim,” indicates that she was head of her own household, in addition to holding a valued position at court. Thousands of years before the advent of the “SheEO,” Tapputi was leaning in and bossing around underlings. She was a master of her craft, and recognized as such by her peers. Much of what we know about her comes from secondary sources, but the process of distilling and refining ingredients to produce a fragrant balm – oil, flowers, water, and calamus, a reed-like plant similar to lemongrass – is described on surviving clay tablets. It's miraculous how modern her scents seem – or rather, it's surprising how little has changed. Tapputi used scent-extracting techniques like distillation, cold enfleurage, and tincture that natural perfumers still use today. She also mixed grain alcohol with her scents, creating perfumes that were brighter, lighter, and had more staying power than anything else available at the time. These scents may have played a religious role in ancient culture, but they may have simply been another way to prettify the body and please the senses.

"Beauty is sharp, it is intense, and it comes at a cost."

Unfortunately, Tapputi's story is a fragmented one – she's possibly the first female chemist, and yet she's been lost to history. There is much more evidence available about the perfumes of ancient Egypt, Persia, and Rome. In 2003, archeologists unearthed the world's oldest known perfume factory in Cyprus. Archaeologists theorize that this mud-brick building and the perfumes it produced caused Greek worshippers to begin associating the island with Aphrodite, the goddess of sex and love. (Born from the magical remnants of the sky god's testicles, which had been separated from his body and cast into the sea by Cronos, the Titan god of harvest, Aphrodite supposedly walked from the foaming waters of the sea and onto the beach at Paphos, an ancient settlement located on the southern coast of the island.) Analysis of the material found on-site revealed that these ancient perfumers were using plant-based ingredients like pine, coriander, bergamot, almond, and parsley, among others.

These perfumes all sound rather pleasant, don't they? I can imagine dabbing almond oil mixed with a bit of bergamot on my wrists, catching a botanical draft of scent here and there as I move. It seems terribly obvious that people may want to smell like plants. Some of the earliest pieces of art represent flowers, leaves, and trees. Studies have shown that we crave symmetry on an unconscious level, and we're drawn to color, so it makes perfect sense that flowers would hold our attention with their Fibonacci spirals and vivid hues. I can even understand why curiosity might compel someone walking along a beach to pick up a chunk of marine fat and sniff it. It's a bit harder to understand the moment when medieval perfumers made the conceptual leap from smelling the glandular sacs of dead musk deer to dabbing it on their pulse points. Yet at some point, this must have happened, for starting after the Crusades, Europeans became obsessed with musk.

Like many prized spices, fabrics, and luxury items, musk came to Europe from the Far East. Derived from the Sanskrit word for testicle, “musk” refers to the glandular products of small male Asian deer. These little sacs of animal juice were harvested from the bodies of slain deer and left to dry in the sun. In its raw form, musk smells like urine, pungent and sharp. But after being left to dry, musk develops a softer scent. The reek of ammonia fades, and it becomes mellow and leathery. It stops smelling like piss and begins to smell like fresh sweat, or the downy crown of a baby's head. It gained a reputation as an aphrodisiac; according to some legends, Cleopatra used musk oils to seduce Mark Anthony into her bed. The size of musk molecules also contribute to its perfume popularity: Larger molecules oxidize slower, so musk's comparatively large molecules last longer than other odors and allow it to extend the life of other scents. Its fixative property means musk is a base note in many perfumes, even ones that don't smell overtly musky.

In 1979, musk deer were listed as an endangered species by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna (CITES), so it's no longer legal to use natural musk in commercial perfumes. However, Tibetian musk deer are still killed for their glands, and a brisk trade in poaching has resulted in some illegal musk showing up online. Musk is also used in some traditional Chinese and Korean remedies, which helps the substance remain one of the most valuable animal products on earth. In his book The Fly in the Ointment, Joe Schwarcz, director of the McGill University Office for Science and Society, points out that musk is “more valuable than gold.”

Civet is a more unknown fragrance, though it also appears frequently in perfumes. Made from the glands of a mammal that shares the name of the scent, civet is similar in structure to musk on a molecular level but smells even more animalistic, according to people who have actually sniffed it. “They have a general odor about them that is very pungent,” says Jacqueline Menish, curator of behavioral husbandry at the Nashville Zoo. Civets are uncommon zoo creatures. They are neither felines nor rodents, though they're commonly mistaken for both. Although few visit the zoo just to glimpse these odd little nocturnal creatures, the Nashville Zoo has several banded palm civets because the zoo director “just loves them.” (You may have heard of civet coffee, a product made by force-feeding Asian palm civets coffee beans, then harvesting them from their poop. Society, it seems, has come up with several odd ways to make money from civet asses.) When they are startled, frightened, or excited, civets “express” their anal glands, and the greasy liquid “shoots right out.” The scent hangs in the air for days. “I guess I could see if it was diluted it might not smell as offensive,” Menish concedes. “But it can be really bad if it hits you.”

Unlike musk, civet can be collected without killing the animal, but it's not a cruelty-free process. Civets are kept in tiny cages and poked with sticks or frightened with loud noises until they react and spray out their valuable secretions. Commercial perfumers no longer use genuine civet in their fragrances, but James Peterson, a perfumer based in Brooklyn, owns a very small vial of civet tincture. “It smells terrible when you first smell it,” he says. “But I have some that is five years old, and it gets this fruity quality as it ages. In a tincture, it gets this rich scent that works wonderful with florals.” On a few occasions, Peterson has used genuine musk or civet to make “tiny amounts” of specialty perfumes, and the resulting blends have an “intensely erotic draw.” Customers report that these dark and dirty smells are potent aphrodisiacs. “When it's below the level of consciousness, that's when it works best,” he adds.

The reek of ammonia fades, and it becomes mellow and leathery. It stops smelling like piss and begins to smell like fresh sweat, or the downy crown of a baby's head.

Like musk and civet, ambergris comes from an animal, but making it doesn't necessarily involve murdering whales. Whales have historically been killed for their bodily products, including their oil, spermaceti, and their stomach contents, but it's more likely now that ambergris is beach-found since it is only produced by an endangered species, sperm whales. The waxy substance forms in the hindgut of a sperm whale to protect their soft interiors from hard, spiky squid beaks. According to Christopher Kemp, author of Floating Gold: A Natural (and Unnatural) History of Ambergris, ambergris begins as a mass of claw-shaped horns that irritate the whale's digestive systems. As the mass gets pushed through the whale's hindgut, it grows and slowly becomes “a tangled indigestible solid, saturated with feces, which begins to obstruct the rectum.” Once it passes into the ocean, it begins to slowly mellow out. The black, tar-like wad is bleached by the ocean until it becomes smooth, pale, and fragrant. It ranges in color from butter to charcoal. The most valuable ambergris is white, then silver, and finally moon-gray and waxy. It's believed that only 1 percent of the world's sperm whale population produces ambergris. It's very rare, very bizarre, and very valuable.

The human appetite for ambergris dates back to ancient times. The Chinese believed it was dragon spit that had fallen into the ocean and hardened, and the ancient Greeks liked to add powdered ambergris to drinks for an extra kick. King Charles II of England liked to eat ambergris with eggs, which was apparently a fairly common practice among the aristocracy in England and the Netherlands. It shouldn't be surprising that people engaged in some light coprophagia – smell and taste are so deeply linked, and while I can't attest to the taste of ambergris, I can say that it smells beguiling. Given the chance, I would sprinkle some silvery whale powder on my eggs, just to see what it was like. (It's certainly no stranger than eating gold-coated chicken wings – another practice seemingly designed to destroy value by passing the desired object through a series of rectums until it reaches the inevitable white bowl.)

In perfume, ambergris is often used to boost other scents. It plays a supporting role rather than a starring one, for although the smell is fascinating, it isn't very strong. It has an unearthly fragrance. It smells like the sea, but also like sweet grasses and fresh rain. It's amazing that something made in the bowels of the whale could smell so pure. If you found fresh ambergris, midnight black and sticky and stinking, perhaps you wouldn't want to eat it. But with distance and dilution, ambergris is transformed from animal garbage to human ambrosia.

Schwarcz's book offers one reason why we're drawn to these scents, citing studies that suggest people with ovaries be more sensitive to musk, particularly around ovulation. He cautiously speculates that musk might resemble chemicals produced in humans to attract potential mates.

Over the phone, he is even more wary of speculating about a possible evolutionary explanation for our fragrance preferences. “The sense of smell has been studied thoroughly with surprisingly little results in terms of what we actually know. It's such a complicated business,” he said. “We don't know why musk is more attractive to some people than others. We don't know why it smells differently when it's diluted, but we know that it does.” When I asked whether we like musk because we're programmed to enjoy the smells of bodies, he was quick to turn our talk toward the issue of pheromones, which “may not actually even exist at all” in humans, despite our desire to attribute various observed phenomenon to the invisible messengers. According to Schwarcz, much of what the general population knows about pheromones only applies to certain nonhuman species. For instance, boar pheromones are well understood, easy to replicate, and used by farmers to increase the farrowing rate amongst their stock. Some of the perfumes that boast “real pheromones,” like Jovan Musk and Paris Hilton's eponymously named scent, may contain pheromone molecules – ones that pigs would find very enticing.

But where science fails to offer a satisfactory explanation, artists can step in, providing an illuminating tool to help understanding our relationship to desire and aesthetics. For perfumer Anne McClain, co-owner of MCMC Fragrances in Brooklyn, it is the tension between foul and sweet that elevates a fragrance from consumer product into the realm of art. This is key when it comes to repugnant ingredients, from indolic florals to musky secretions. The indecent element becomes a secret of sorts, a gruesome piece of marginalia scribbled alongside the recipe, visible to only those in the know but appreciated by all. The foulness whispers below the prettiness, and combined, these various elements create a scent that smells paradoxically clean and dirty, light and dark.

“Indole is what makes the scent of jasmine interesting,” she says. “It makes you want to come back and smell it again – it has an addictive quality to it.” Unlike citrus scents, which are one-note and rather simplistic, florals have an element of decay, a whiff of putridity. McClain rightfully points out that this is part of what makes flowers themselves attractive to bees and other pollinators. Corpse flowers famously smell like dead bodies, but so do many other blossoms, just to a lesser extent.

Plus, humans are by nature “just a little bit gross,” McClain says. Like civets, musk deer, and whales, we shit, we secrete, we mate, and sometimes we vomit. But we also give birth and create beauty, and for McClain, it's this life-giving ability that links blossoms and humans. “I think there is a depth to anything that is made of life and creates life. There's something inherently sexual in that,” she says. “Even though something like civet will smell gross on its own, it adds an element of reality.” When layered properly with other olfactory delights, this can create an evocative smell, one that you want to return to, to interrogate with your nostrils the same way you might pore over a painting. Through layering pleasure on top of disgust, perfumers can create something that resembles life – exquisite, fleeting, and mysterious.